Other Dim Sum Dishes

Dim sum, also known as Yum Cha, has evolved from simple and coarse to abundant and refined. As a major component of southern Chinese cuisine, the elegance and richness of dim sum is astonishing. With the help of Unfamiliar China, you’ll be able to understand the stories behind all kinds of Cantonese dim sum snacks, as well as professional, detailed instructions for how to make them.

Unlike the tea customs of other areas, Cantonese people usually take their tea with dim sum snacks. Cantonese people’s feelings toward morning tea can be summed up with the saying “a cup of tea and two dim sum snacks are all you need to be happy”. Below, we’ll introduce you to all manner of dim sum snacks that you’ll commonly find in Cantonese tea houses. The abundant variety of dim sum reflects the fastidious attitude that Cantonese have toward their food.

What are the Different Types of Dim Sum?

Cantonese dim sum can be divided into three main categories:

- local snacks from what is known as the “Lingnan” geographic area which includes Guangdong and Guangxi

- dim sum made with wheat flour (noodles, buns, etc.)

- western-style pastries.

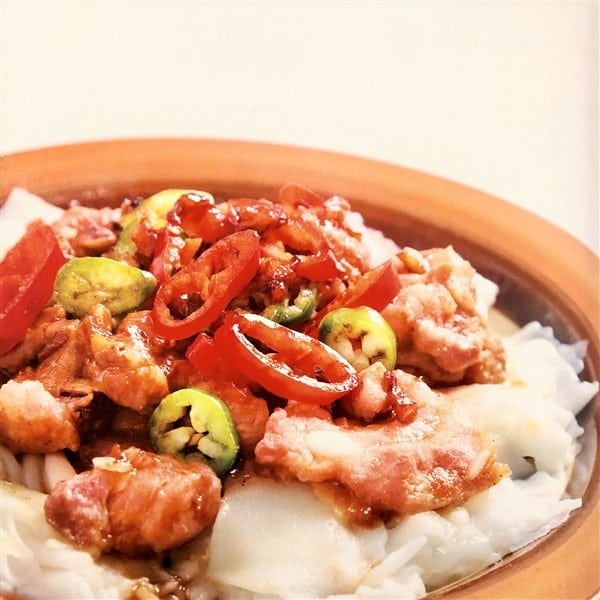

In southern China, rice is the primary staple food. That’s why in Cantonese dim sum, many of the local snacks from the Lingnan area are made from rice and grain products. Examples include sesame balls (Jian Dui), Zongzi, rice-flour cakes, Fun Guo (steamed dumplings), Lo Mai Gai (sticky rice with chicken), as well as sticky rice cakes with fillings of coconut, sesame, or peanuts; and buns with flour made from yam, taro, and other ingredients.

After the Qing dynasty, as Guangzhou’s prominence in foreign trade grew and merchants from the north began to pour in, flour dishes that suited the tastes of northerners began to appear. Examples include baozi & mantou (buns), wonton, shumai, and noodles. Through continuous refinement, these dishes evolved into classic Cantonese dim sum snacks imbued with the distinct flavor of the Lingnan region.

The Silent Communication Code in Dim Sum Restaurants

During the late Qing era, many wealthy aristocrats would stroll down to tea houses in the morning carrying bird cages. According to legend, there was once a patron who, after having finished his tea, placed his canary into the empty teapot and called the waiter over to refill the water. When the waiter opened the teapot lid, the canary flew away. The patron, insisting that it had been an expensive Atlantic canary, cheated the tea house out of a large sum of compensatory money. After that incident, the tea house created a rule stating that before patrons could have their tea water refilled, they had to open the lid of the teapot themselves and the server would come to add water.

Of course, this is only a legend, but this custom still exists today. This saves the server the effort of two trips and prevents the need for patrons to shout for the waiter rudely. After the bill has been paid, the waiter will turn the teapot lid upside down to indicate that table has already paid. This subtle form of communication is another manifestation of the refinement of Cantonese morning tea.